Professor Koji Fukui,

Laboratory of Molecular & Cellular Biology, Department of Life Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, Shibaura Institute of Technology

“Staying youthful and healthy forever”—surely a universal wish. In this two-part interview, we speak with Professor Koji Fukui, who has been at the forefront of aging research for over 25 years at Shibaura Institute of Technology.

In Part I, we explore the two aspects of aging, its underlying cause—oxidative stress—and Professor Fukui’s core philosophy of “preventive medicine.” We also hear about the moment that sparked his career path and delve into the foundations of his unwavering curiosity, which underpins the research results to be discussed in Part II.

—Professor, as an alumnus of Shibaura Institute of Technology, many might not associate the university with biology. Were you already researching aging as a student?

Professor Fukui: People are often surprised and say, “Biology at Shibaura?” But I’ve been conducting experiments using rats and mice since I was a student. I’ve been involved in aging-related research for over 25 years now.

The turning point came during my student years, thanks to my academic advisor at the time. He had previously worked at what is now the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology—a central hub for aging research in Japan. Under his guidance, I entered the world of aging studies.

But my interest in biology really dates back to childhood. My mother was a nurse, so I spent time in hospital nurseries and was always around nurse uniforms at home. That environment naturally sparked an interest in medicine and biology early on.

After university, I became a researcher at Wakayama Medical University, where I conducted clinical studies using human samples. Later, I became an assistant professor at Hokkaido University, where I fully immersed myself in neuroscience, particularly neuron research. My academic journey spanned experiments on animals, human samples, and cultured cells—each giving me a new perspective.

Then in 2008, I heard that my alma mater, Shibaura Institute of Technology, was launching a new Department of Life Science. As a graduate, I was invited to apply—and I took the challenge.

In 2014, I spent a year at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the U.S., specifically at the National Institute on Aging (NIA), where I deepened my expertise in aging research. Looking back, it’s clear I’ve been consistently pursuing the theme of aging my entire career.

—You’ve studied aging for many years. How do you perceive its mechanism?

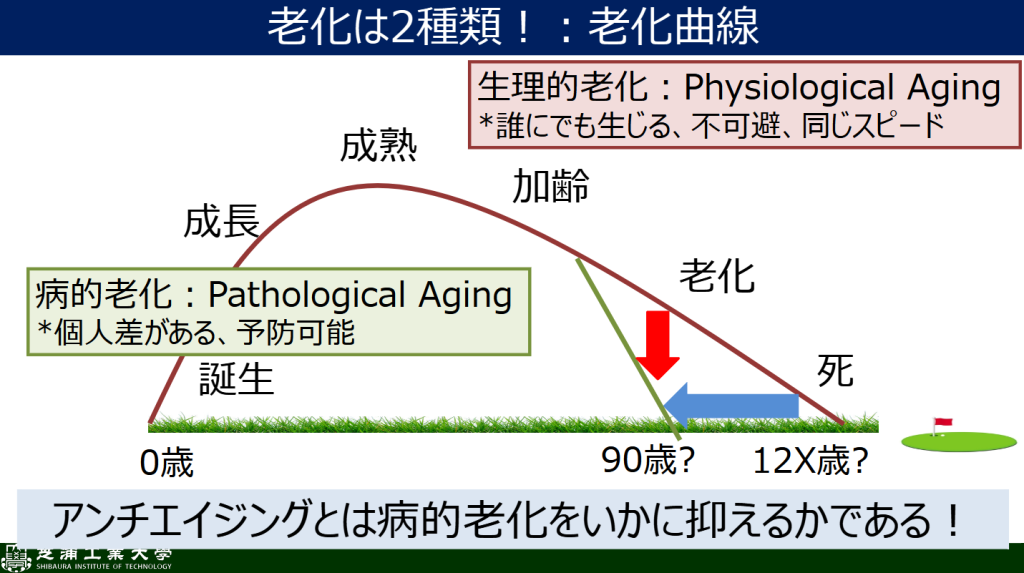

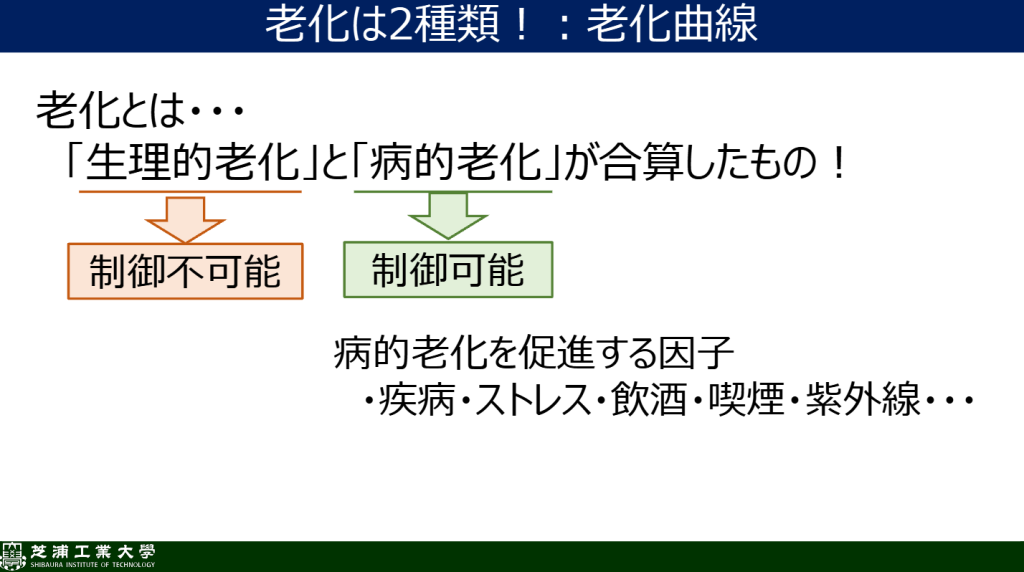

Professor Fukui: Aging can be viewed from two different aspects. The first is “physiological aging”—a natural, unavoidable process that progresses at the same pace for everyone. No amount of supplements, exercise, or healthy lifestyle can change that.

The second is “pathological aging,” which varies among individuals based on lifestyle and other factors. What we usually refer to as “anti-aging” or “delaying aging” targets this type. Among aging researchers, this distinction is considered common knowledge.

Our research group works on the hypothesis that a major cause of pathological aging is oxidative stress. This idea isn’t new—it was proposed about 70 years ago by Dr. Denham Harman. Today, global research societies on oxidative stress exist, with thousands of researchers investigating how oxidative stress promotes aging and disease.

However, the term “oxidative stress” may still be unfamiliar to the general public, as it addresses not visible symptoms like cancer or Alzheimer’s, but the underlying causes. Nonetheless, at any academic conference, you’ll hear oxidative stress mentioned. Whether it’s a central or peripheral focus is the only difference.

Compared to 30 years ago when I began, public awareness has grown immensely. Back then, people simply accepted aging as inevitable. Now, terms like “rusting of the body” are used in TV commercials, and the concept of oxidation in the body is more familiar to the public.

Scientific understanding has also progressed. While we’ve long known that reactive oxygen species oxidize proteins and DNA, solid evidence linking that to aging and disease was once lacking. But today, global research efforts are steadily revealing clear evidence that oxidative stress indeed accelerates aging and causes various diseases.

—How do you select research themes in your lab?

Professor Fukui: Our basic motto is to value a “preventive medicine” approach. Drug development is important, but drugs treat illnesses *after* symptoms appear. I believe it’s better to prevent disease before it causes suffering.

That’s why we focus especially on natural ingredients—not synthetic chemicals, but substances found in everyday foods. If we can maintain health just by consuming such natural ingredients, that’s ideal. It feels safer too, since we’re not introducing foreign compounds into the body. I’m drawn to the idea of discovering these “hidden treasures” in foods.

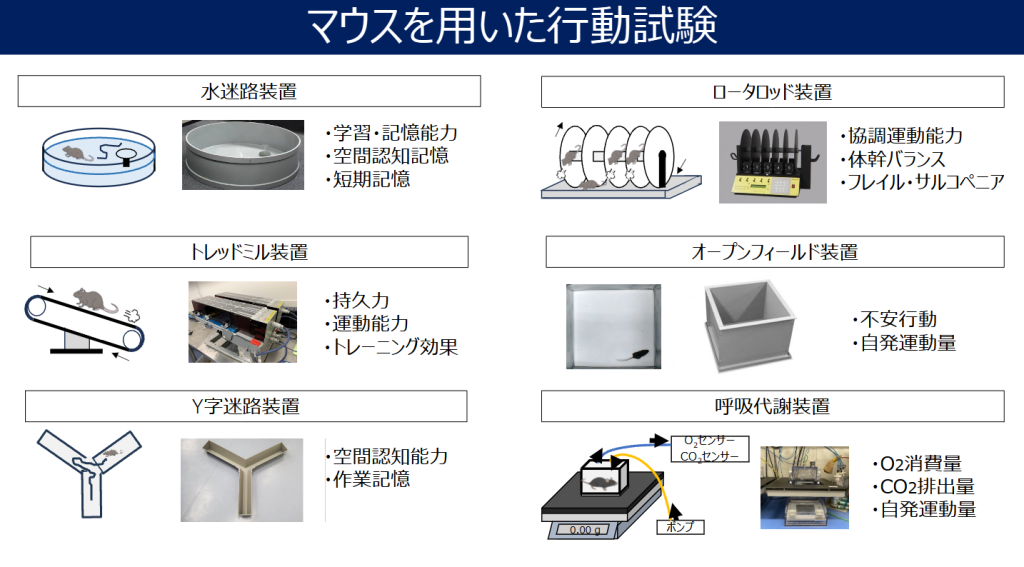

Our lab’s greatest strength is our comprehensive evaluation systems. Since I returned to Shibaura in 2008, we’ve built robust setups for cultured cell studies. This allows us to evaluate changes at the micro level in cultured neurons as well as macro-level behavioral changes like learning and memory in mice. That comprehensive scope is a major advantage.

We also have extensive behavioral test equipment. For example, we own six different devices for evaluating learning and memory like the Morris water maze—equipment usually housed in shared university facilities. But we own them all independently.

Of course, just having the equipment isn’t enough—you need years of expertise. It’s like sushi craftsmanship; the techniques can’t be learned overnight. Thankfully, many companies request us to test whether their ingredients improve cognition, but we’re currently so full with projects that we often have to turn them down (laughs).

Ultimately, when choosing research themes, what matters most to me is whether I find the topic intellectually exciting and personally engaging. That sense of curiosity fuels all my research.

In this interview, we explored aging mechanisms from the perspective of oxidative stress and rediscovered the importance of preventive medicine through diet. Professor Fukui’s work continues to shed light on the antioxidant power of everyday foods—paving the way for a future where many can enjoy healthier, longer lives.

In Part II, we delve into Professor Fukui’s encounter with Twendee X, a supplement that made him exclaim, “This might actually work!” What were the surprising results that even impressed him? We’ll also explore serendipitous lab discoveries and the future of dementia research. Don’t miss it.

Laboratory of Molecular & Cellular Biology, Department of Life Science,

Faculty of Science and Technology, Shibaura Institute of Technology

307 Fukasaku, Minuma-ku, Saitama 337-8570, Japan

https://sit-mcblab.sakura.ne.jp/